Rebuilding the Past

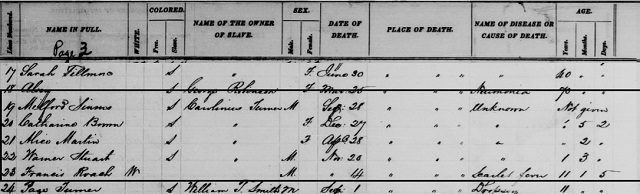

Death Records from 1853

April 6, 2017

Yesterday, I spent most of the day in Richmond. I had a meeting with the director of the American Civil War Museum. Last year, the week before our Civil War Weekend, we took President Lincoln (Ron Carley), General Grant (Curt Fields) and General Lee (Thomas Jessee) to see the museum and the Confederate White House. We had met the director during that time and he asked that we contact them when we did our next event in 2017.

I spoke to him yesterday about possibly having President Lincoln come and do an appearance before our June 3rd and 4th Civil War Weekend this year. He suggested that we make an appearance at the 1861 Tredegar Gun Foundry in Richmond. This location has more people and more open space for the appearance. Now I need to contact the Education Director for the museum and President Lincoln to see if we can mesh up schedules.

My meeting went earlier and a little faster than I had planned, so I had some time on my hands before returning to Belle Grove. I decided to hit up the Library of Virginia’s records to see what more information I could pull around our enslaved community.

Back in 2012, just before we got into Belle Grove, I had done tons of research on the people and the location. One of my stops was at the Library of Virginia. I found so much there. And I spent hours there! One thing I found at that time was Death Records for King George County. I wanted to go back and get a better copy of these records and see what more I could find.

I pulled the death records and hoped there were more than what I found last time. The information was from 1853 to 1870. But sadly, only the years 1853, 1854, 1855, 1857 and 1859 were available. The rest of the years were either missing or had no information.

After arriving home last night, I complied this information and created some display pieces to place in the museum. As I typed the information in, I found myself sadden by what I saw. Most of the deaths were children under the age of 2. The oldest death on record was Charles Washington at the year of 55. He died of an ulcer to his hand. I also found the names of the parents. How touched I was to see some of these parent’s names appearing again and again. What loss they endured.

But the hardest thing to see was the entries of slaves with just a first name. Then the cause of death to be listed as “unknown”. In some cases, the date of the death wasn’t known either. Then the ones who they didn’t know the parents or in case just to know the mother’s first name.

I think this is why this part of history has become so important to me. These people were born here, lived here and died here. Nothing was recorded for most of them. There is no grave marker that say “I was here.” No newspaper announcement. No fanfare. And the only way I know about them is the meager information that was listed.

In looking at the lists, I am sorry, but I think there had to be more that weren’t reported. There had to be. You can see diseases coming to the plantation and taking so many around the same time. Who else didn’t make the list? Who else is now lost to time.

One of the things I really want to do is to find the slave cemetery. There are no markers here. And to date, I haven’t found anyone that can point me to where it was. But yet, I have a feeling I know. Don’t ask me how, I just do. I really want to find someone with access to a ground penetrating radar so we can check and see. We don’t have a lot of extra funds available. All the foundation money is going to save the outbuildings. But if we can determine where it is, we can fence it off and have it consecrated. We may not know who is there, but at least we can say they were here.

My next step is to take these names and start doing some research on them. Maybe there is some connections somewhere. Who knows where it will lead me. What surprises I have in story. But it is a journey that needs to be taken, a journey that must be taken.