Turners Period Ends at Belle Grove

Well the past three days have been somewhat of an odyssey. As I started to prepare the next chapter of Belle Grove’s history, little did I know that I would run into so many road blocks. You would think that as we got closer to the present time, information would be easier to come by. But that doesn’t seem like the case with Belle Grove’s history. I was able to find more from the 1670 – 1860’s than I have been from the 1860’s to the present. And what is so amazing its that I know that records during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War were destroyed or lost. But at least we are capturing what we can before it is lost to time.

Before our “working vacation”, we had last posted about the letter requesting amnesty to President Johnson from Carolinus Turner for his role in the Civil War. From this letter we found out that Carolinus Turner’s wife, Susan August Rose Turner had an uncle, Captain William Jameson that had served in the U.S. Navy during the war. Since then I have found out that she also had two brothers that served in the Civil War, Alexander Rose, her older brother and Dr. William Rose, her younger brother. Both served in the war and both were killed. I haven’t been able to find out which side they served on yet.

Carolinus and Susan would live at Belle Grove and have five children, Caroline “Carrie” M. Turner, Anna August Turner, George Turner, their only son, Susan Rose Turner, and Alice Pratt Turner.

Carrie Turner would marry Dr. William N. Jett in 1874. Dr. Jett was a widower with six children from his first wife, Virginia Mitchell. Dr. Jett and Carrie would have their own child, George Turner Jett in 1876. Dr. Jett, Carrie and Virginia Mitchell and three of Dr. Jett’s and Virginia’s children are buried at Emmanuel Episcopal Church located just as you enter Belle Grove Plantation.

Anna Turner would marry Captain Robert L. Robb in 1869. They would have five children. Here is a note on Robert Robb. His mother, Frances Bernard Lightfoot was the daughter of Sarah “Sallie” Bernard Lightfoot, daughter of Frances Hipkins Bernard for whom the current mansion at Belle Grove was built for. One of their children, Carolinus Turner Robb would pass away just under two years old. Anna Turner Robb is also buried at Emmanuel Episcopal Church.

Sarah “Sallie” Bernard Lightfoot

Daughter of Frances “Fannie” Hipkins Bernard

Grandmother of Robert Robb

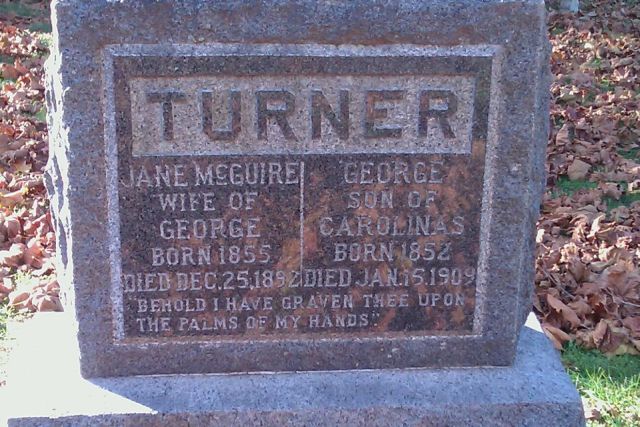

George Turner would marry Jane Murphy McGuire in 1876. They would have nine children. George and Jane are also buried at Emmanuel Episcopal Church along with their son Edward McGuire Turner and daughter Susan Rose Carter Turner Mitchell.

Alice Pratt Turner would marry George B. Matthews in 1875. They would have one daughter, Alice T. Matthews.

Susan Rose Turner would marry Frederick Campbell Stewart Hunter in 1874. Frederick was a lawyer in King George and would go on to become a county judge in 1880s. They would have three children, son Frederick Campbell Stewart Hunter, daughter Caroline C. Hunter and son Thomas Lomax Hunter. Thomas would grow up to do some wonderful things in his life. He would attend William and Mary College in Williamsburg and Georgetown University. In 1908 he would pass the Virginia bar and work as a lawyer in King George, Virginia. In 1929, he started writing a column for the Richmond Times-Dispatch called “As It Appears to the Cavalier”. He would write this column until his death in 1948. He also published a book called “Columns from the Cavalier” in 1935. He would serve as a delegate in the Virginia House of Delegates for King George from 1918 to 1920. During World War I, he would serve as a food administrator for King George. He was given the honor as Poet Laureate of Virginia in 1948.

All three of Susan and Frederick’s children were born at Belle Grove Plantation. None of the Hunter family is buried at Emmanuel Episcopal Church. From what I have put together Susan and Frederick lived at Belle Grove with her parent from the time they were married.

In 1876, Carolinus Turner would pass away at the age of 64. He would pass away from consumption. Consumption is just another term for tuberculosis. Thanks to one of our readers, I now have a copy of Carolinus Turner’s obituary that appeared in the Alexandria Gazette on December 19, 1876 that was reprinted from the Fredericksburg Herald:

“DEATH OF A PROMINENT CITIZEN OF KING GEORGE

The many friends of Carolinus Turner, of King George Co., will regret to learn of his death, which occurred on Monday last at his home in that county. Mr. Turner was a large landholder, and previous to the war, owned a great many servants. He was a gentleman of excellent education, and commanded the respect and esteem of a large circle of friends.”

After the death of Carolinus Turner, it seems that Susan, his wife moved from Belle Grove to one of their other properties. From a Federal Census in 1880, I found her living alone as a widow in King George with just one laborer and one servant.

At his death, Carolinus was buried at Emmanuel Episcopal Church. The land for this church was donated in 1860 by Carolinus. Just in front of his grave is also the grave of Susan Turner’s mother, Anna August Rose who passed away in 1853. Susan Turner, wife of Carolinus Turner would pass away in 1891. However, she is not buried with Carolinus or her mother. I have not been able to find where she is buried at yet.

One note on the Church: From the deed record I recently found from the Central Rappahannock Heritage Center, when Port Conway was established there was a previous church area listed on the deed. It makes me wonder if Emmanuel was raised over a previous church site that already had a cemetery attached to it. This would explain why Anna Rose was buried there in 1853 before Emmanuel Episcopal was built in 1860.

I have not been able to find a will for Carolinus Turner. As prominent as he was, I don’t think he would have died without one. But at this time, we don’t have a copy of one. I do know that Belle Grove was passed to Susan and her husband Frederick. They would live at Belle Grove until 1893.

There is also a court case in which a property called “Smith Mount” in Westmoreland County was said to have been given to George Turner Jett by Carolinus Turner. In this case dated 1895 between William N. Jett, Guardian verse George Turner Jett it states that Susan Turner give to William Jett in 1878 a lot in Port Conway that had a house on it. It was for the use and benefit of Caroline M. Jett, his wife during her life and then for the benefit of Dr. Jett. It was to be given to whoever Caroline designated by deed or will of Caroline. However Caroline died without a will in 1883, leaving one child, George Turner Jett who was now 20 years old. His only property was “Smith Mount” given to him by his grandfather Carolinus Turner. It states that the Port Conway lot is small and more suitable for a businessman. Dr. Jett at that time lived 18 miles from “Smith Mount” and wants to sell it. (I am not sure if that means Dr. Jett wants to sell “Smith Mount” or the lot at Port Conway) But George Jett is a minor. It then lists George Jett as a defendant. My guess would be that Dr. Jett wants to sell “Smith Mount” and wants George to move to Port Conway. But it looks like George doesn’t want to do so. I don’t know the outcome of this case yet.

One more note on George Turner Jett. I have found his name listed on a college catalog for William and Mary College for the session between 1991 and 1992. At the time, George would have been 15 or 16 years old. It doesn’t say if he graduated or not.