Chatham Manor – The Civil War Years

Continuing from Wikipedia:

The Civil War brought change and destruction to Chatham. At the time the house was owned by James Horace Lacy {1823-1906}, a former schoolteacher who had married Churchill Jones’s niece. As a planter, Lacy sympathized with the South, and at the age of 37 he left Chatham to serve the Confederacy as a staff officer. His wife and children remained at the house until the spring of 1862, when the arrival of Union troops forced them to abandon the building and move in with relatives across the river in the beleaguered city of Fredericksburg. For much of the next thirteen months, Chatham would be occupied by the Union army; they referred to it as the “Lacy House” in their orders and reports, as well as diaries and letters.

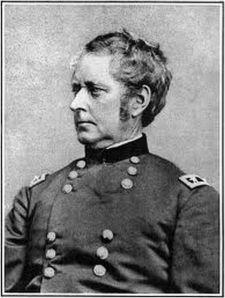

Northern officers initially used the mansion as a headquarters. In April 1862, General Irvin McDowell brought 30,000 men to Fredericksburg. From his Chatham headquarters, the general supervised the repair of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad and the construction of several bridges across the Rappahannock River. Once that work was complete, McDowell planned to march south and join forces with the Army of the Potomac outside Richmond.

President Abraham Lincoln journeyed to Fredericksburg to confer with McDowell about the movement, meeting with the general and his staff at Chatham. His visit gave Chatham the distinction of being one of three houses visited by both Lincoln and Washington (the other two are Mount Vernon and Berkeley Plantation on the James River east of Richmond.) While at Chatham, Lincoln went to Fredericksburg, walked its streets, and visited a New York regiment encamped on what would become known as “Marye’s Heights” during the later battle.

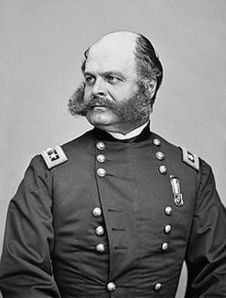

Seven months after Lincoln’s visit to Chatham, fighting erupted at Fredericksburg. In November 1862, General Ambrose E. Burnside brought the 120,000-man Army of the Potomac to Fredericksburg. Using pontoon bridges, Burnside crossed the Rappahannock River below Chatham, seized Fredericksburg, and launched a series of bloody assaults against Lee’s Confederates, who held the high ground behind the town. One of Burnside’s top generals, Edwin Sumner, observed the battle from Chatham, while Union artillery batteries shelled the Confederates from adjacent bluffs.

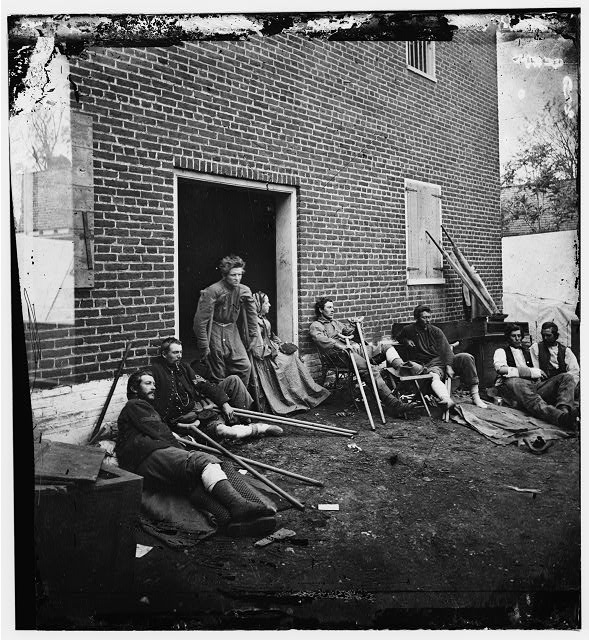

Fredericksburg was a disastrous Union defeat. Burnside suffered 12,600 casualties in the battle, many of whom were brought back to Chatham for care. For several days, army surgeons operated on hundreds of soldiers inside the house. Assisting them were volunteers, including the poet Walt Whitman and Clara Barton, who later founded the American chapter of the International Red Cross.

Whitman came to Chatham searching for a brother who was wounded in the fighting. He was shocked by the carnage. Outside the house, at the foot of a tree, he noticed “a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc.-about a load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near,” he added, “each covered with its brown woolen blanket.” In all, more than 130 Union soldiers died at Chatham and were buried on the grounds. After the war, their bodies were removed to the Fredericksburg National Cemetery. Years later when three additional bodies were discovered, the remains were buried at Chatham, in graves marked by granite stones lying flush to the ground.

In the winter following the battle, the Union army camped in Stafford County, behind Chatham. The Confederate army occupied Spotsylvania County, across the river. Opposing pickets patrolled the riverfront, keeping a wary eye on their foe. Occasionally the men would trade newspapers and other articles by means of miniature sailboats. When not on duty, Union pickets slept at Chatham; Dorothea Dix of the United States Sanitary Commission operated a soup kitchen in the house. As the winter progressed and firewood became scarce, some soldiers tore paneling from the walls for fuel, exposing the underlying plaster. Some of the soldiers’ pencil graffiti is still visible, with additional scrawls being deciphered by Park Service staff.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker served the wounded at Chatham. Walker was awarded the Medal of Honor, the only woman from the Civil War to be so recognized, for her meritorious service to the wounded during several battles. When the law for the Medal of Honor was changed to restrict the medal to combat veterans, the US government asked her to return hers. She refused and died with the medal in her possession. Her family continued to petition for the full restoration of the honor. In 1977, then-President Jimmy Carter signed the Congressional bill into law that restored Dr. Walker’s medal.

Military activity resumed in the spring. In April, the new Union commander, General Joseph Hooker, led most of the army upriver, crossing behind Lee’s troops. Other portions remained in Stafford County, including John Gibbons’ division at Chatham. The Confederates marched out to meet Hooker’s main force and for a week fighting raged around a country crossroad known as Chancellorsville. At the same time, Union troops crossed the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg and drove a Confederate force off Marye’s Heights, behind the town. Many of 1,000 casualties suffered by the Union army in that 1863 engagement were sent back to Chatham which again served as a hospital.

By the time the Civil War ended in 1865, Chatham was desolate and severely damaged. Blood stains spotted the floors, graffiti marred its bare plaster walls and sections of the interior wood paneling had been removed for firewood. In addition to the damaged house, the grounds had suffered. The surrounding forests had been cut down for fuel, the gardens and several of the outbuildings where damaged or destroyed, and the lawn had been used as a graveyard. In 1868 the Lacys returned to their home. Unable to maintain it properly, they moved to their house known as “Ellwood” and sold Chatham in 1872.

Part Three – The Later Years

Please visit our Facebook Fan Page

to see more Virginia Historic Homes

a lot of good information!!!! Thanks for sharing !

You are so welcome! It was fun going!

I love looking at those old pictures.

Me too! Of course any history is good history for me!

Your posts are like cliffhangers for me…waiting for the next revelation!

It’s coming! I have to have something to bring you back 😉

Eventually you should turn these historical posts into a book about Belle Grove. You will have a ready audience with your guests and blog visitors. Keep up the great work!

Thank you! I hear that all the time! I think I just might have to do it!

What a story! Horrible, terrible and nearly as tragic as the War itself. Thank you for sharing it with us.

You are so welcome! There is more to come!

I suppose there’s some irony in the fact that when enemy soldiers abused beautiful homes such as Chatham with graffiti, those actions would, more than a century later, result in enhanced historical meaning for those structures..

You know it happened a lot during the Civil War. I have been to many buildings and seen it.

The old photographs are priceless. I wish I was magic and could step into them , step back in time. You and your husband are doing almost that with this amazing project. Virginia

Thank you Virginia! You know I don’t know if I would want to be around for the Civil War. It was pretty bad.

It was not the best of times. V.

I agree with Gracious Posse, your historical posts deserve to be published. Thank you so much for educating us!

Thank you! I am thinking about it.

Such important information!

Thank you!

Wonderful research – and very interesting,

Thank you!