The Heart of the Plantation and Root of Southern Cuisine

August 10, 2015

When we started this campaign “Save Our History at Belle Grove” on GoFundMe, I started looking around the internet for information on Summer Kitchens, Slave Cooks and Food from the South. As a southern girl from South Carolina and a chef here at Belle Grove, food and cooking is truly in my blood.

When people ask me why did I become a Bed and Breakfast owner, my response tells it all.

“My grandmother was a grand southern lady, who taught me three things. Entertaining, Cooking and History. It was inevitable that I would become a bed and breakfast owner.”

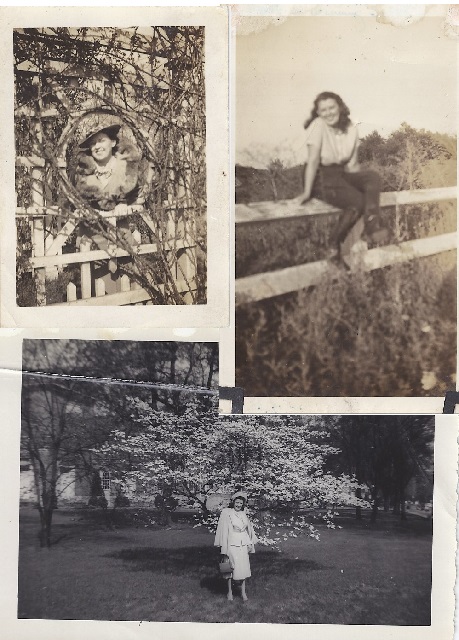

Betty Ann Dickinson (Hutto) – My Grandmother “Nannie”

So I want to share with you the history around where Southern Food came from and how the Summer Kitchen was truly the heart of the plantation.

I came across an article written in Deep South Magazine called “The Root of Southern Cuisine” by Beth McKibben (December 3, 2012). In this article she is interviewing Atlanta Chef Todd Richards. At the time he was working at The Shed at Glenwood. According to their website, he doesn’t work there anymore.

In their article, they discussed Southern Food and Slavery. Chef Richards had given a talk at the Atlanta History Center’s Folklife Festival inside a slave cabin the previous September 2012 around slavery and Southern Food. He had offered little known facts about slaves and root of southern food.

One fact that was presented in the article:

“And guess what? It ain’t all fried chicken and gravy laden biscuits. In fact, true Southern food is neither fatty nor simple. It’s clean, complex and most importantly, born form the economics of survival.”

According to the article:

“Restaurants around the country try and often fail at presenting truly authentic Southern cuisine. They doll it up with gravies, hot sauces and fry everything that isn’t nailed down in the kitchen. Then, they slap it on a plate and call it “Southern.” For Chef Richards, Southern is more than its Cracker Barrel image, with slavery at the very root of its beginnings. To know its history is to understand Southern food.”

Here are some of the questions and answers from the article:

BM: So you believe the country is reverting back to more straightforward, simpler foods?

TR: Southern food is really not that simple. It is an essential American storyteller along with our government and music. It has a long history. Southern food encompasses many regions, people and economics. It’s good, healing food born from strife and survival. The slaves weren’t creating Southern cuisine in order to make history, they were cooking to stay alive.

BM: How did the slaves influence Southern cooking? What were the typical ingredients they were working with at the time?

TR: You have to look at two things: what came with the slaves on the boat and what they had to work with when they got to America. There was a strong Native American influence in the early beginnings of Southern food when slaves began arriving: crops like corn and techniques like frying. Then, you have crops and techniques that came over from West Africa with the slaves, like the peanut (or goober peas), okra (or gumbo) and stewing techniques. There’s also daily survival ingredients like watermelons, which served as canteens in the fields. It’s 95 percent water. The slaves also used the rind as soles for their shoes. So ingredients like this that are now part of Americana and the Native American influence really started shaping Southern food very early on. But you can’t discount other influences like that of the Spanish and Portuguese through Louisiana or the Latin influence through parts of Texas. The slaves worked with what was available to them and adapted their daily diets accordingly.

BM: So, through a diet based on survival, the slaves really transformed Southern foodways into what we see today?

TR: What people don’t really understand about Southern food is that it is all based off of preservation methods. How can we keep the food for the longest period of time and make sure it’s safe to eat? Africans never ate beef until it was introduced to them in America. Fish, vegetables, fruits were the diets of most African people. Salting and frying meats and vegetables were simply preservation methods they learned from the Native Americans. They adapted to survive, while in the process, unknowingly transforming the Southern diet with the ingredients they brought with them from Africa. They found that they could grow these crops quite well here in the South.

BM: We know slaves were cooking these meals for themselves but do you believe the slaves began to cook using their native ingredients for their masters, or do you believe that began to occur during Reconstruction?

TR: Yeah, they were definitely cooking these meals for their masters. I mean, the thing about Southern food, when it’s cooking, it smells good! I’m sure they brought the best cook up to the house and left the more undesirable portions for themselves.

BM: What Southern cooking technique that survives today can be traced back to the slaves?

TR: Definitely one-pot cooking. Gumbo, cornbread and hoecakes were being done out in the fields. There were no lunch breaks. But, to me, the most essential technique to come out of slave-based cooking is preservation. How the food was preserved is what made it taste so good. But they weren’t thinking about that at the time. The economics of survival was the slaves’ only motivation. Preservation methods are truly what transformed Southern cooking to what we know it to be today.

BM: How did preservation methods influence the flavors?

TR: To me, greens tell the unique story of Southern food. There was no refrigeration, so slaves used meat, mostly pork, and salt to preserve the greens by laying the meat on top. Not only did the pork preserve what was underneath, but it flavored it as well. They didn’t necessarily eat the meat after the greens were finished. They might repurpose it. Frying was another technique. Many people are shocked to learn that fried chicken is not Southern-born but actually Scandinavian and Native American. Animals in West Africa were not fatty. It was hot; they didn’t require fat to stay warm. Frying was a preservation method the slaves adopted.

I found this out when I was up in Louisville, Kentucky, researching Native American foods. They were teaching the method to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. It was meant to preserve the meat underneath the skin during long journeys. They would fry rabbits, squirrels, small game birds in bear oil. Slaves in certain regions of the South caught on to this method, finding the skin of the chicken, for instance, to be quite tasty. Jerky is another example of preservation turned tasty snack in the fields. You take the meat off the bottom of the shank, slice it very thin and dry it out on tobacco leaves. They learned this preservation method from the Native Americans, because in the early days of slavery, Africans knew little of preserving meat. The slaves economically had no choice but to stretch every last morsel of food they had. Food preservation is the key to all Southern cooking. It is the essential ingredient.

BM: What do you want people to know about slaves and Southern food?

TR: Southern cuisine is regional and really can’t be categorized under a big umbrella. Key ingredients like greens and preservation methods are the great equalizers in our story but, after that, it’s all regional.

Georgia and Alabama Southern is totally different from Appalachia Southern. Frying is more prevalent in the colder climates of the South than in the Deep South. They have more animals with fat on them whereas in Georgia, for instance, it’s warmer and so our native animals are leaner. Where would the slaves have gotten the oil to fry the chickens? They didn’t reach for a bottle of peanut oil like we do now. Those influences came into the picture much later. There are more cornbread recipes in Georgia and Alabama than in the Carolinas, where rice is more prevalent. In Appalachia, stews are more common. The slaves knew how to preserve and cook with what nature had to offer. Each region had its own micro-climate and trade routes. The food of the South is as diverse as its people.

BM: Do you believe that your slave ancestry has influenced your cooking? Any special family recipes that were passed down?

TR: I don’t really have any family recipes that were written down, but I do know how my family constructed meals. My grandmother and great-grandparents were fantastic cooks. Family meals were big when I was growing up. They were like celebrations. We had barbecue every summer, prepared by my Dad. Everything revolved around food, even the gifts we gave to one another. But there were two different Southern influences in the family. I can’t tell you exactly where each side comes from in the South, but I can tell you the region by the way they cook. My Mom’s side is more Appalachia/Carolinas/Ohio with stews, rice and frying. Whereas my Dad’s side uses smoking methods and vinegars when cooking, like in the mid-South. I can tell my family’s story through food. So essentially, my Dad’s more cornbread, my Mom’s more biscuits.

I’ve never really thought about this before, but I just discovered my family tree through what I do every day: food. This is my family tree.

To read more of this article, please visit Deep South Magazine’s Website

http://deepsouthmag.com/2012/12/the-real-roots-of-southern-cuisine/

A special thank you to Deep South Magazine for allowing us to reprint some of this article.

Today, we are still raising money for our “Save Our History at Belle Grove” GoFundMe campaign. At present we have just $3,856. A far cry from our needed $45,000.

In May, 2016, we will be holding our Civil War Weekend. This weekend, we will be conducting a “Civil War Bootcamp”. This “bootcamp” will encompass all parts of life during the Civil War time period. Not only will we have reenactors encamped on the grounds, but we will have reenactors to talk about plantation live. It is our hope to have at least the Summer Kitchen completed in time for this event. What a wonderful way to reintroduce this priceless piece of American history and the heart of the Southern Plantation to the general public. We hope to have reenactors to play the enslave people and to tell their story as well.

Help us get our “Heart of the Plantation” beating again.

Save Our History at Belle Grove GoFundMe Campaign

Please consider donating whatever you can. No donation is too small and every penny counts in this effort.

Then help us by sharing this blog and sharing our campaign with your friends and family. We can only raise this money if we have everyone help us spread the word.

Thank you so much for all your support and encouragement. We truly appreciate everyone!